Fashion, Film, and Gothic Grief…

How luxury, beauty, and pop culture reveal what we're really afraid to say out loud.

Frills hide fangs, silks mask sins.

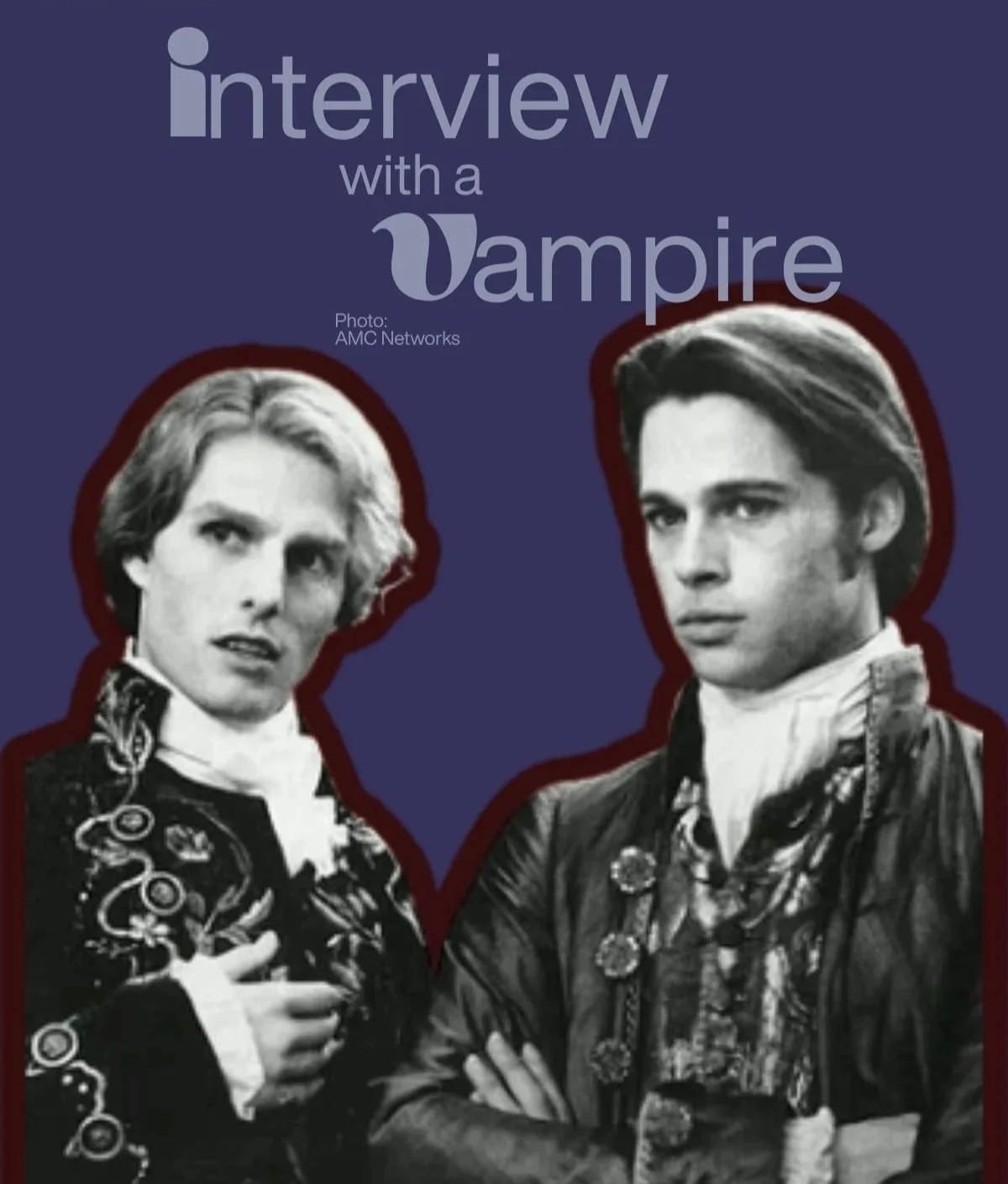

Theatrical excess reveals raw grief. / gliss•studio / AMC Networks

There's a moment early in the film Interview with the Vampire where Louis materializes across the room in a split second, startling the young, naive, and eager journalist. A goofy, equally abrupt sound effect accompanies his supernaturally swift movement. I've watched this scene countless times. It still tickles me. Yes, I actually giggle every time I see it.

The 1994 film wants me to be scared. I find it ridiculous instead. Oddly enough, that ridiculousness doesn't diminish the story. It truly amplifies it. What's actually absurd is the premise of vampirism itself: that inheriting superhuman gifts somehow negates a person's inherent and lived humanity. Louis and Lestat, the duo at the center of the story, both struggle with loneliness, abandonment, and self-loathing. The theatrical excess doesn't obscure these emotions. It makes them impossible to ignore.

Gothic Excess as Truth Serum

When we talk about Gothic excess, we're really talking about beauty. Late 1800s beauty. Turn-of-the-century opulence. Observe Lestat's frilly collar and embellished coat, Louis's shining silken vest with beaded details, and even the pimp who attacks Louis in the dark alley wearing a beautiful coat over dirty clothes. This speaks to the monstrosity of the age itself: the beginning of industrialism, when humans devalue and debase each other while dressed in stunningly crafted garments. The vampires aren't separate from this historical moment. They embody it. The character of Claudia was inspired by Anne Rice's daughter Michele, who died of leukemia at the age of 5; Rice wrote the novel in five weeks in the aftermath. What reads as melodrama is actually grief channeled through supernatural metaphor. Literary scholarship notes that Gothic melodrama deliberately “polarizes and hyper-dramatizes forces in conflict” to mobilize scenes of “high feeling.” The excess is the point.

The Excess is the Point

This theatricality didn't just captivate readers—it spawned a cultural phenomenon. The novel sold over 8 million copies worldwide, and the 1994 film adaptation grossed about $223 million globally, unusually high for a vampire film of its era. The franchise continues through AMC's Interview with the Vampire television series and related tie-in events, including concert presentations built around Daniel Hart's operatic score. Yet beneath the camp and opulence lies Rice's raw grief, making the absurdity a perfect vessel for human truth.

Louis's Exquisite Blindness

This gilded world unfolds against the Deep South's macabre backdrop: plantation opulence masking profound moral rot. Louis owned slaves there. His hands weren't clean. Yet he's horrified at the monstrous nature of “life” as a vampire. He mourns his dead wife and child while hundreds of enslaved people maintain his lifestyle of drinking, gambling, and self-pity. He’s quite self-absorbed, just like most other humans. Hmmm. The vampire transformation doesn't create his moral blindness. It grants him an eternity to continue it. And Lestat? Lestat is Louis's mirror, but even so, Louis refuses to truly see or to look within.

In one scene, Lestat drains a woman completely while her companion sits in drunken ecstasy, blind to her own danger. Louis watches silently until Lestat demands he finish what they started. “You're a killer,” Lestat yells. “It's your nature.” Louis feels genuine horror watching Lestat's cruelty. But up to this point he has only killed twice as a vampire: first, the house slave Yvette, in what appears to be an accidental loss of control due to extreme hunger (he has been avoiding feeding on humans by substituting their blood with rats), and then avoiding blood on his hands again until Claudia, a young orphan girl whom Lestat turns to emotionally trap Louis. Louis only frees his slaves after becoming a vampire and accidentally killing one. Becoming the monster he feared forces him to acknowledge the monstrosity he was already living. He then proceeds to burn down the plantation in a fabulous fury.

The Two Burnings

Louis expresses his suppressed emotions with destructive fire twice in the film. First, he burns the plantation after freeing the slaves. Second, he sets fire to the Parisian vampire coven that executed Claudia. In the first burning, he's like some odd combination of the spiteful wife and angsty teen. When confronted about destroying their lavish home, he tells Lestat, “You thought you could have it all.” In the second burning, centuries later, he's stone-cold and composed. Resolute and resigned. Seemingly justified.

Here's what strikes me: in both cases, he chooses destruction over building something new. Even after centuries of immortality and profound loss, his emotional response remains fundamentally the same. Psychology research shows generational trauma often manifests as “recurring patterns of behavior that stem from unresolved traumas,” where survivors either repeat the cycle or create a new narrative. Louis receives the “dark gift” of eternity, and yet he chooses repetition. Immortality doesn't elevate Rice's vampires. It merely grants them forever to repeat the same mistakes. The Gothic excess, the theatrical beauty, the absurd sound effects when Louis materializes across a room—all of it magnifies this truth rather than obscuring it. That's why I keep watching. That's why it still tickles me.

The more monstrous they become, the more human they appear.

Brands are human, and humanity doesn’t exist without good stories.

Ready to evolve your story?